Emma (BBC – 1972)

Emma (1996)

Emma (A&E – 1996)

Clueless (1995)

Emma Woodhouse, a child of privilege, is so proud of her successful matchmaking of her ex-nanny to respectable Mr. Weston that she sets out to find partners for the other inhabitants of her small town. She adopts Harriet Smith, a girl of lesser birth, as her next project, and chooses for her the parson, Mr. Elton, ignoring the girl’s interest in a simple farmer. This infuriates Mr. Knightly, an old and close friend of the family and the lord of the manor. In tutoring Harriet on the fine arts of high society, Emma and Harriet frequently go on visits to the poor and infirm, often encountering Miss Bates, a nearly senile old maid who has recently had her beautiful and accomplished, but overly secretive niece, Jane Fairfax, come to stay with her. With her plans going less than smoothly, Emma is distracted by the arrival of Frank Churchill, a charming man who immediately shows an interest in her. It is just a matter of time before relationships are formed, secrets are revealed, and even Emma’s hypochondriac father is as contented as he can be.

There is a similarity between all the stories of Jane Austen. Someone previously unacquainted with her work couldn’t be faulted for arriving at the conclusion that Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Emma were all adapted from the same source material. Narrowing our focus, both Emma and Pride and Prejudice follow a strong-willed, witty, single, young woman dealing with questions of marriage and social position. Her world is that of the lesser rich, wealthy, and obscenely opulent: even those who are greeted with sympathy for their humble state have servants. The most powerful man in the area is romantically interested in her, but prejudices, pride (see where the title comes from) and misunderstandings stand in the way of a happy resolution. She must also deal with an absurd parent and the advances of an inappropriate suitor. Then a tall, dark, and handsome stranger comes to town, a man that is not what he appears to be and has a number of secrets. He befriends our heroine, much to the distress of the lord of the manor. The details of who will marry whom (the only subject of the stories) are worked out at a series of dinner parties, dances, carriage rides, and daytime visits, with very little passion and absolutely no eroticism. Certainly the two works have major differences, but they have more in common than not.

Where these two differ is in tone. Pride and Prejudice is a cross between a romantic drama and a satiric comedy. Emma is all satire. It reveals an idle and self-absorbed upper class where the greatest tragedy is not being asked to dance. The workers go completely unnoticed and must slavishly answer to the whim of people who are incapable of taking care of themselves. While Pride and Prejudice has a few farcical characters for comic relief, everyone in Emma is ludicrous to some degree. For some it is shown in everything they say or do; Emma’s father bemoans the poor state of anyone getting married or having a baby as it is bound to give them a severe chill. For others, like Emma herself, it is most evident in an over inflated manor of speaking. It is hard to find a line that isn’t ironic. This makes Emma a much lighter viewing experience.

The trick with any adaptation is to make the humor shine, and to make Emma likable. The first can be difficult because there is plenty of droll dialog, but little that’s laugh-out-loud funny. The second is even harder due to Emma’s numerous flaws. Austen thought that no one would like Emma except Austen herself. After all, the character is vain, prejudiced, simplistic, domineering, shortsighted, and a busybody on a massive scale. But then everyone in the story shares at least one or two of those traits, and often to a much greater degree. Do you have to like Emma to like the story? Yes. You spend too much time with her and her concerns. If you dislike her, there’s no motivation to stick with it, and most of the humor falls flat.

Emma (BBC – 1972) – Doran Godwin/John Carson

The earliest “film” version you are likely to find (previous made-for-TV adaptations are unavailable), the 1972 BBC Emma is a 6-part miniseries running 240 minutes. It is the choice of your average Janeite (devoted fans of Jane Austen’s writings who tend to have little patience with changes to their beloved author’s works) since it sticks closely to the book, cutting little. With so much time to work with, character relationships are clearer than in the later versions and plot points that could be foggy (particularly in the Gwyneth Paltrow film) are explained, sometimes repeatedly. For anyone studying the story, this is a huge advantage, but for simple entertaining viewing, it can be tedious. Multiple times, I found that the scene I’d just watched could have been removed from the series with no loss of information or emotion. Some of the jokes are run into the ground. Mr. Woodhouse’s incessant harping on drafts and disease was amusing for a time, but long before the end I was praying for one of the often mentioned viruses to finish him off. Likewise, Miss Bates’ prattle crosses the line between fun and annoying. The filmmakers showed more concern with matching the book than for what works best on the screen.

Emma ’72 is more successful than its competitors as satire. It is clear from the first moment that there is something odd about these people. Everyone speaks their lines in a staccato fashion, making it all feel unreal. These aren’t actual people, but the representations of the silly qualities of people. That makes it almost drama-free, but also the least charming of the three available Emmas.

Class distinctions are highly visible, with great deference given to those of higher station. The common rich folk display bizarre levels of joy whenever Emma deems to grace them with a word. Mrs. Elton’s greatest sin (and she has many) is here seen to be not keeping to her place in society.

Is Emma likable? Yes, from the start, although your affection for her is likely to waver sometime later, at least for a time. Her questionable behavior is explained by her place in society. Since the rich and mighty are always silly, and no one but Mr. Knightly has ever been in a position to correct her, it is no surprise that a good natured girl would have some faulty views on how to carry out her good deeds. Plus, since it is all artificial, it is hard to feel that she is ever hurting anyone.

Doran Godwin is an amicable Emma, though some of her facial movements, particularly with her eyebrows, are difficult to interpret. It is almost as if the director told her to change her expression, but didn’t say to what, so she chose randomly. It is hard to determine her age, but while she may be in her early twenties, she looks somewhat older. Similarly, John Carson appears to be ten years too old to be Mr. Knghtley. He brings dignity to the part, but not warmth.

As for the rest of the cast, Robert East fits the role of the roguish Frank Churchill, although he doesn’t overwhelm. Timothy Peters is too handsome for Mr. Elton, and fails to take advantage of the comical opportunities. Debbie Bowen’s Harriet Smith is more child-like than I’ve seen elsewhere, making it easy to accept that this flibbertigibbet would hang on Emma’s every word and do whatever she said. The others do acceptable jobs, but no one is memorable.

Since it was shot for British television (and in the ’70s), don’t look for exciting camera work, diverse music, or extravagant sets. It resembles an old episode of Masterpiece Theater. If that doesn’t ring a bell, think of the production as somewhere between a big screen release and a live play.

Emma (1996) – Gwyneth Paltrow/Jeremy Northam

Playing up the light comedy angle over the satiric, the 1996 screen version is more concerned with the characters than its predecessor, and while not a romantic-comedy, it is closer to being one than the others. It is as if they were making a companion piece to Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

Two hours shorter than the miniseries, it trims much of the Frank Churchill/Jane Fairfax plot in favor of the Harriet Smith/Rev. Elton one. If this is your introduction to the story, you are likely to need a second viewing to determine who Jane is related to, why she is there, and what Frank is up to. Jane has almost no personality, and Frank only makes an impression because he is played by Ewan McGregor with great flamboyance. It seems that writer/director Douglas McGrath watched Clueless, where the Frank character is gay, and decided to one-up that. It works for the reduced screen time.

While this is a pastoral, almost fluffy picture, the eccentricities of all the characters have been dialed down, as if they are meant to approach normalcy. Mr. Woodhouse’s hypochondria falls within believable limits for bizarre older relatives. Harriet Smith (Toni Collette) is an average, weak-willed girl placed amongst her betters, and Mrs. Bates is an annoying, lonely, elderly woman not unlike many you will meet in your life. Only Frank (as previously mentioned) and Elton (Alan Cumming, who captures perfectly his humorous pomposity and oozing sycophantic nature) are more peculiar than in the BBC series.

Unfortunately, this nearing-reality approach makes Emma’s behavior harder to excuse. Since the class differences (still visible) are not played up quite so strongly, we’re left with Emma just being a haughty brat who does real emotional damage to those around her. Sure, it all works out in the end, and Gwyneth Paltrow’s substantial charm makes it impossible to dislike Emma, but it takes far too long to care about her.

If Emma is harsher, Mr. Knightley strikes a more congenial note. Still a judge of Emma, his criticisms (and the tones he uses to deliver them) are reasonable. Jeremy Northam’s performance gives this version its more romantic flavor.

Emma ’96, released theatrically, far exceeds the others in look and sound. It is a larger production with more elaborate sets, lush colors, and music that fits every moment. It should be no surprise that TV versions can’t compete, but it is a good looking picture by any standard.

Emma (A&E – 1996) – Kate Beckinsale/Mark Strong

Released a few months after the Paltrow/Northam Emma, it is hard to imagine that the makers of this TV movie weren’t intimidated by their much bigger sister. However, it acquits itself well.

Kate Beckinsale is a warm and caring Emma, with a child-like glee. Her mistakes are those of a kid who is still learning how the world works. While not as graceful as Paltrow’s, she is also not as distant.

Thematically, A&E’s Emma stands between the other two. It is more obviously a satire, with the characters behaving weirder than on the big screen, but not as bizarre as in the miniseries. It is more fantastical (showing us Emma’s daydreams), but is also grittier. These people got dust in their hair and mud on the hems of their gowns.

Once again, cutting was necessary (this is a TV movie, not a miniseries). Here, Harriet Smith and Mr. Elton get short shrift. Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax take the lion’s share of the story. That trade works as there is more depth and intrigue with Frank and Jane. It works even better because of Raymond Coulthard, whose Frank is charismatic enough that his actions, and the acceptance of those actions, are easy to believe. Even though there is more material in the earliest version, this is the best and most complete accounting of Frank.

I’d give my nod to this rendition for having the finest mix, but it stumbles where the theatrical Emma was steady, with Mr. Knightly. He steps out of the absurdity, and is played as a straight, dramatic character, and an unpleasant one at that. He scolds and lectures without any sign of affection, and often in a manor which is not only unseemly, but no fun to watch. The idea of this winsome, innocent Emma getting together with this tyrannical Knightly is tragic. Romance fans will have little to cheer about. Happily, the focus of Emma is not on that relationship.

Clueless (1995) – Alicia Silverstone/Paul Rudd/Brittany Murphy

Emma goes modern and teen and it’s never been treated better. Clueless is smart, witty, engaging, and more fun than a barrel of Beverly Hills teens. Austen’s dialog may be hard to find, but her characters, plot, and spirit are easy to spot.

Emma has become Cher Horowitz (Alicia Silverstone, delightful in every way), the queen of her high school’s in-crowd, whose successful matchmaking of her teachers is incentive for her to try again. Harriet is now Tai (Brittany Murphy), a lower class girl from the East who doesn’t know that “It is one thing to spark up a doobie and get laced at parties, but it is quite another to be fried all day.” Cher tries to set Tai up with Elton (Jeremy Sisto), who is pretty much Elton. Some things never change. Of course, Tai would fit better with skateboarder Travis (Breckin Meyer), but Cher doesn’t see him as a member of fit society. Naturally a good looking stranger comes to town, although his name is Christian instead of Churchill, and while he looks to be a good match for Cher, it is clearer than in other Emmas that they will never be a couple. As for Knightly, he is Josh (Paul Rudd), whose brotherly connection to Cher is every bit as confusing as Knightly’s has always been to Emma.

Many of the scenes play out as Jane Austen fans would expect. Elton asks for Cher’s picture of Tai, and later tries to pick up Cher on the ride home from a party. Josh asks Tai to dance to save her from embarrassment. Christian rescues Tai from attack. Tai sits with Cher to burn her treasures from her “relationship” to Elton, etc. If you know the story, you can guess how things will play out.

But it is also fresh. The dialog, an invention based on high school slang that then became actual teen slang, is hysterical and quotable:

“As if!”

“That’s Ren and Stimpy. They’re way existential.”

“Christian said he’d call the next day, but in boy time that meant Thursday.”

“Unfortunately, There was a major babe drought at my school.”

“That was way harsh”

“I felt impotent and out of control. Which I really, really hate.”

“Wasn’t my mom a total Betty?”

Clueless is the all out satire that Emma is meant to be, but it also works as a romantic comedy. The key, besides the sharp screenplay, is Alicia Silverstone’s Cher. I don’t usually use the word “adorable,” but I couldn’t help thinking it during much of my latest screening. My wife, who has no hesitation with the word and sat with me during all of my many viewings since I first saw it on the big screen, must have said “Isn’t she adorable” ten times. And so she is. Her less than lofty deeds do not damn her as she has several motivations running simultaneously, and somewhere in the mix is the real desire to do good. For a story about shallow people, Cher is anything but two dimensional.

Few comedies are as repeatable as Clueless. It has the right actors, a stylish director (Amy Heckerling, who is also responsible for Fast Times at Ridgemont High), a tight, funny script (also by Heckerling), bouncy, integrated, music, characters you care about, and Austen’s novel as a base.

There’s been a lot of Jane Austen on film recently. Since 1995, in addition to the Emmas, there have been five versions of Pride & Prejudice (Pride and Prejudice ’95, Pride & Prejudice ’05, Pride and Prejudice: A Latter Day Comedy, Bride and Prejudice, and Bridget Jones’s Diary), two Sense and Sensibilitys (Sense and Sensibility, Kandukondain Kandukondain), Mansfield Park, and Persuasion.

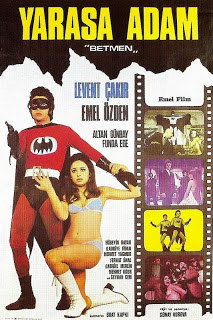

So, if you watch a Batman movie and say, “That’s all well and good, but where are the strippers and why doesn’t Batman shoot anyone in the face?” then you’ve found your film. All the Turkish rip-off films focus on old-school, manly-men and hot women and this film leans into that strongly. Hitting women? Sure. Killing villains? Absolutely. I know very little of Turkish culture, so I can only speculate on if they thought of superheros as adult entertainment, or if they are more laid back about breasts and blood for kids.

So, if you watch a Batman movie and say, “That’s all well and good, but where are the strippers and why doesn’t Batman shoot anyone in the face?” then you’ve found your film. All the Turkish rip-off films focus on old-school, manly-men and hot women and this film leans into that strongly. Hitting women? Sure. Killing villains? Absolutely. I know very little of Turkish culture, so I can only speculate on if they thought of superheros as adult entertainment, or if they are more laid back about breasts and blood for kids.